History

John Hus was a professor of philosophy and rector of the University in Prague. He was the foremost of Czech reformers and was eventually accused of heresy and burned at the stake on July 6, 1415.

The reformation spirit did not die with Hus however as the Moravian Church, or Unitas Fratrum (Unity of Brethren), as it became officially known was established by his followers in 1457 when they gathered in the village of Kunvald, about 100 miles east of Prague, in eastern Bohemia, and organized the church. (This was 60 years before Martin Luther.)

There then followed a time of growth, persecution (particularly during the Thirty Years War;1618-1648) and exile; however the church continued to develop.

The prime leader of the Unitas Fratrum in these difficult years was Bishop John Amos Comenius (1592-1670). He became world-renowned for his progressive views on education. Comenius, lived most of his life in exile in England and in Holland where he died.

In due course some Moravian families fleeing persecution found refuge on the estates of Count Zinzendorf’s in Saxony, Germany and in 1722 they established the community of Herrnhut. The new community became the haven for many more Moravian refugees and in 1732 the first missionaries were sent to the West Indies.

Count Zinzendorf meets King George II

After coming to England to seek permission from the King to travel to the Colonies the Moravians established work in England and subsequently in Ireland.

John Cennick was a prolific preacher who pioneered the Moravian work in the north of Ireland and laid the groundwork for the establishment of first and only complete Moravian Settlement in Ireland at Ballykennedy, Co Antrim, subsequently called Gracehill in 1759.

John Cennick

In the 18th century the village was highly structured, all the inhabitants belonging to the Church. They were divided into different groups or “Choirs” each with specific duties and dwelling places, hence for example, the single brethren and sisters’ houses and the widows’ cottages. There were also houses for married people and families. The residents followed trades and crafts for the benefit of the Settlement. The intention was that the Settlement should be self-sufficient and support its outreach work.

The Moravians were renowned for their high standard of education and there were for sometime, day and boarding schools for both boys and girls.

Gracehill Village 1829

Life in the village nowadays is, of course, very different to the 18th century, but the layout of the buildings and the unique Georgian style of architecture remain very much the same. The Moravian Church remains central to the village, facing the square and flanked by the Manse and the Warden’s House. The brothers and sisters walks, on either side of the Church, meet at the burial ground or “Gods Acre” which, is still in use today.

Gracehill was designated a Conservation Area in 1975 and has won many awards including the Europa Nostra Award. The Settlement is currently working towards designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site with other international partners in Germany, Denmark and USA.

An active Moravian Congregation continue to meet at Gracehill and to this day maintain the tradition of a Congregational Diary. The Church is home to “The Moravian Archive of Ireland” which contains documents and diaries from a number of Irish congregations dating back over 250 years. The diaries are a rich source of information and historic details shedding light not only on the day-to-day lives of the residents but also on the impact of momentous national and international events on the community.

Roberta Thompson and Jackie Neill – Archivists.

The late 18th century was a particularly turbulent time in Ireland and the Gracehill diaries record, in fascinating detail, the trials and tribulations and ultimately wonderful example of the Gracehill community during the 1798 United Irishmens Rebellion.

GRACEHILL AND THE UNITED IRISHMEN

By the summer of 1798 the situation in Ireland had reached the point of no return and there was an uprising across the country against the Government by a group known as the United Irishmen. The Gracehill diary entry for Thursday, the 7th of June 1798 states. “Soon in the morning reports came from all quarters that the United Irishman were rising in our whole district, and they were soon observed marching over the fields with their Pikes, guns, pistols, and other weapons with the intention to go to take Antrim.”

And it is further recorded that, “at 6 o’clock in the evening, the rebels took Ballymena [nearby town] after a fierce but short engagement and made the military prisoners.”

There were also reports that the United Irishman intended to destroy Gracehill and this was no idle threat as the chapel of the nearby Galgorm Castle was burnt at this time, and in fact remains a ruin to this day.

The diary goes on, “Saturday the 9th June proved a very turbulent day, Randalstown, six miles distant from us was seen in flames.”

Despite such alarm, independent contemporary report states “Gracehill was the only village in the whole district, which had not been infected by the insurrectionary spirit, and the kind, and peaceful deportment of the inhabitants towards their very enemies, where under God, the principal means of preserving the settlement from destruction.”

As stated the local town of Ballymena was one of the first towns, taken by the United Irishman, and thereafter men, women and children fled to Gracehill for safety. Subsequently, however, the military were victorious in the County town of Antrim and so when the news reached Ballymena that “the Kings soldiers” were coming towards the town the United Irishmen and their supporters in their turn also fled to Gracehill.

The Battle of Antrim

In the eloquent words of the period another observer records, “As success declared itself in favour of either party alternately, the friends of both were at a loss whither to fly for safety. To the surprise of the Brethren, Gracehill became the general asylum.”

[They] “filled the square. Rebels and Kingsman lay close to each other in the same distress, and were both treated with humanity by the inhabitants. It happened, that some flying along the streets, threw their purses and money into the houses sure of their being restored by the unknown inmates. Such was the confidence of all, in those honest, Christian people.”

And the records state that “On that day, Sunday, the 10th of June 1798, the morning service did not commence until 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and then Moravians, churchmen, (that is Anglicans), Presbyterians and Roman Catholics knelt down together to thank God for his care of them all.”

The Sermon was based on the text for the day, Psalm 71 verse 14. “I will hope continually and will yet praise thee more and more.”

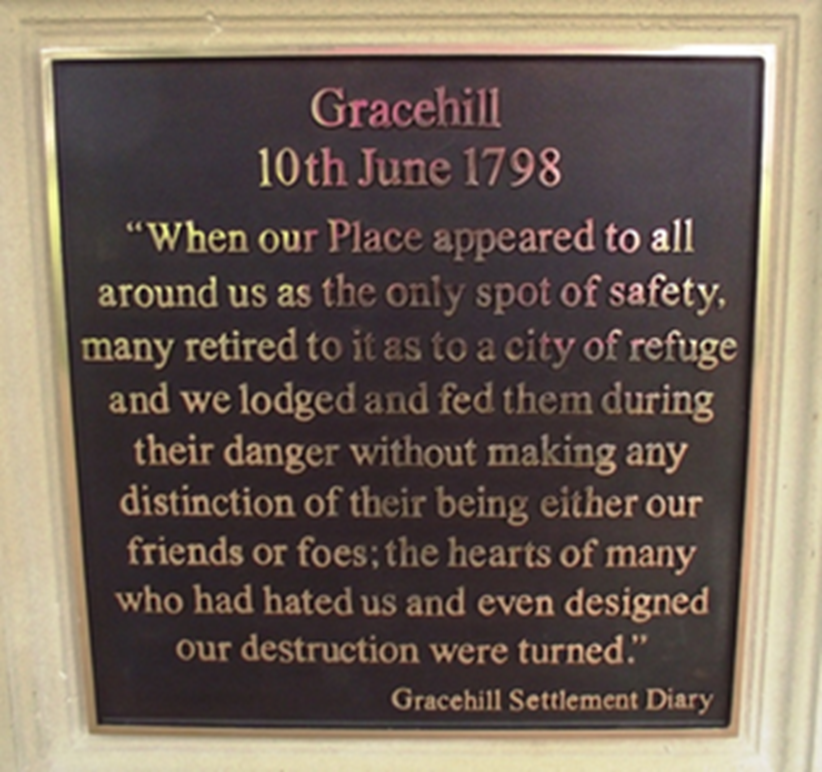

Gracehill’s minister, the Rev John Steinhauer summarised the days events thus; “When our place appeared to all around, as the only spot of safety, many retired to it as to a city of refuge and we lodged and fed them during the days of their danger, without making any distinction of their being either our friends or foes; the hearts of many who had hated us and even designed our destruction were turned.”

Gracehill Settlement Diary - Gracehill 10th of June 1798

Gracehill, with its Moravian ethos, was accepted as a place apart by all sides and in turn, became a place of safety for all sides. The Moravians tolerant and accepting approach, universally acknowledged, was highly unusual at that period in history and particularly so in the turbulent setting of a bloody rebellion and its aftermath in Ireland.

A little over 225 years ago the small Moravian Settlement of Gracehill became an unwilling participant in the momentous and bloody events that swept the length and breadth of Ireland. But despite the alarm, anxiety and fear, the Moravian heritage of faith and service found practical expression in unity, tolerance and care, in a way that resonates in the world even to the present day. In Gracehill, the historic events of June 1798 are commemorated with an obelisk in the Settlement Square, engraved with the minister's words, but the tradition of tolerance and reconciliation lives on, an example and a message that is as important and relevant for the world today as it was in 1798.

1798 Walk & Obelisk Gracehill Square

This is my song”, is a poem written by Lloyd Stone (1912–1993)

Gracehill Trust video featuring pupils from the Ballymena Learning Together. "This is my song", is a poem written by Lloyd Stone (1912–1993). Lloyd Stone's words were set to the Finlandia hymn melody composed by Jean Sibelius. It is a song of peace. Here it is sung to the famous Irish tune "Danny Boy".

"This is my song, O God of all the nations, A song of peace for lands afar and mine. This is my home, the country where my heart is; Here are my hopes, my dreams, my holy shrine; But other hearts in other lands are beating with hopes and dreams as true and high as mine."

Ballymena Learning Together is a collaborative initiative between the eight post-primary schools in Ballymena, Northern Ireland. By working together the schools aim to promote a welcoming community in which young people feel a sense of belonging and where diversity and difference are seen as enriching and valuable. The vision is of a society where young people from differing traditions and cultural backgrounds can work together towards a shared future characterised by mutual understanding and respect.

Gracehill remains a place where people can come together.